by John Duffy

The amount of lift, or whether it occurs all, depends on several factors:

1. Wind Strength – The greater the strength of the wind usually the more lift.

2. Wind Direction – This can alter the lift’s strength, smoothness and turbulence. Wind at 45° or more to the face of a ridge significantly reduces lift and increases turbulence.

3. The Shape of the Ridge – No ridge is perfectly smooth nor is it or running always in the same direction. Wind will funnel up gorges or valleys and slide through gaps. This “Venturi Effect” will speed up the wind in these areas. When the wind is at an angle to spurs, smaller ridges or other protruding parts on the main ridge it can produce areas of strong uplift on the parts facing into the wind with turbulence and even sink behind.

4. Gradient – Some areas are steeper than others. Air will slide around peaks and flow faster where the ridge is smoother and less obstructed. A very steep area can cause the wind pattern to break into turbulent eddies below the crest in front of the ridge.

5. Ridge Surface – Changes in topography and vegetation will tend to spoil the laminar flow of the air over the ridge. Sometimes smaller or smoother parts of the ridge produces as much lift as higher, rougher or more vegetated areas.

6. Height – As we move away from the ridge face the airflow is less obstructed and the lift will get smoother and weaker. Conversely if we sink below the ridge top we can move into turbulence and eddies that can result in considerable sink there depending on the ridge steepness and shape!

7. Landscape – Areas upwind in front of the ridge can determine the smoothness and the amount of lift. The best ridges will have unobstructed wind flow. This is why the best sites are overlooking oceans, lakes, large valleys or inland plains (e.g. Mt Kaputar). Where there are other ridges or landform features in front then the lift may be weak and turbulent.

8. Thermal Lift – If the ridge is facing into the sun this can be a trigger for thermals with the wind helping to break the thermal away from the face. Similarly if there are thermal sources (e.g. ploughed or dark paddocks) upwind in front of the ridge the rising air can get pushed up against the ridge by the prevailing wind giving better lift in that area. On quite large ridge faces like we have along Main Arm Valley lift generated by the heating of these slopes can accelerate up the face producing ridge-like lift even on calm days. To utilise this you may have to fly much closer above the cliff face.

Power Station North Coorabell Ridge

Coorabell Range

History

In the first week of 1936, members of the Brisbane Gliding Club took their three sailplanes and a winch to Byron Bay. The members had been flying circuits in the sailplanes from Eagle farm Aerodrome for some time and considered that it was time to attempt some slope soaring. They had discovered a site on the Coorabell Range about 10 miles inland from Byron Bay where a ridge 600 ft high offered a beat of several miles in an onshore wind. Their three gliders named Pegasus, Robin and Miss Queensland were taken to the site by trailer and the camp was set up on top of the ridge.

Pegasus Glider

The field was small but adequate, and although launches could be made only to a few hundred feet, this was sufficient to contact the lift along the ridge. Several successful though unspectacular soaring flights were made and club members gained valuable experience.

Another expedition to the Coorabell Range was planned for the following year. A group of 28 members and friends set out from Brisbane on Boxing Day 1936. Pegasus had been fitted with a two way radio and on a number of flights was able to exchange messages with members on the ground. This added to the interest and excitement of the flying.

The first good soaring day was Monday, 28 December 1936 when the wind gave good lift along a beat of about 3 miles. With a friend as passenger, Ted Parr soared in Pegasus for 49 minutes, establishing an Australian record for two-seater sailplanes. A maximum height of 1500 feet was achieved during the flight.

Friday 1st of January, 1937, produced a good soaring wind and Ted Parr decided to make an attempt to raise the two-seater record with a really worthwhile flight. A young local lad, aged about 12 years, had been very active in helping the club members during their holiday camp and Parr invited him to occupy the rear seat of the sailplane during the flight. Lift was good along the slope and Parr had no trouble staying up, he finally landed after five hours 1 minute, having reached a maximum height of 2000 feet, to find he had established a new Australian duration record for sailplanes. While Pegasus had been soaring, Doug Henderson was launched in Robin and also achieved a maximum of 2000 feet. He landed after three hours 15 minutes because he developed cramp in his right arm which interfered with his flying. This flight exceeded the previous best solo flight by a glider in Australia, breaking the record set by Howard Morris in 1931.

The club members were delighted with these achievements and rightly proud of the pilots involved. The gliding camp was to be crowned, however, by yet another record. On Sunday 3rd January, the final day of the camp, Billy Spiller set the duration record for a woman pilot in Australia by soaring Pegasus for 75 minutes with Ted Parr as passenger.

Sources: Doug and Elaine Henderson

Brisbane Telegraph, Geoff Richardson

Coorabell Ridge

Opposite Mullumbimby

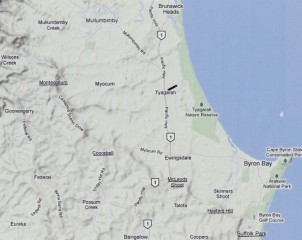

This ridgeline, directly behind Tyagarah Airstrip, works in north to easterly wind directions. Tyagarah strip is NE facing (05). To be able to soar the on the ridge the wind strength needs to be 15 to 20 kts depending on its direction. A good indicator of whether or not it is likely to be working is if there are whitecaps on the ocean in front of the airstrip.

If the pressure differential over the inland is too high the “seabreeze” can stall or stop between the strip and the ridge then, although there are whitecaps, there’s nothing working on the ridge. You have been advised!

The centre of the ridge from the highway lookout at McCloud’s Shoot to Possum’s Shoot near Coorabell directly opposite the strip works in most directions, especially from the north-east. The southern end from the highway lookout, through Hayter’s Hill to Suffolk Park, works best with a strong northerly component whereas the northern end to Montecollum, where the hang gliders launch from, works well in north-east to easterly breezes. Heights of 1600’ and more are attainable along these sections. The northern part of the ridge after this from the power station just past Mullumbimby and beyond is quite broken. These parts are still usable in ideal conditions where heights over 2000’ have been achieved.

Source Google Maps

Northerly winds can produce some lift (thermal too) off the north facing slopes of Mount Jerusalem and Mt Boogarem at the northern end of Main Arm Valley and the cliffs along this valley will give good lift in the right wind conditions up to 2500’ in some places, and some interesting turbulence in other parts.

Flying the Ridge

The front ridge varies in height but is approximately 600 ft high in the centre. Working the ridge low down you will find that the lift is quite close in and you will need to follow the ridge contours carefully flying fairly close to the crest, or in some places Coorabell Road itself, to stay in the strongest lift. The lift band here is narrower and you must fly accurately and smoothly while always keeping the speed of your MotorFalke glider at or above 50 kts to prevent being caught too close to the stall in any turbulence or wind sheer. If you are at 600 to 700 ft and you execute a sloppy turn or turn too far out from the ridge then you can easily drop below the ridgeline into more turbulent air or even lose the lift altogether.

If this happens you may have to consider a motor restart. It’s amazing what it does to your peace of mind to have a good consistent couple of hundred feet of height above the ridge top. If I’m working weak lift for a period of time level or just above the ridge I will occasionally restart the motor so that it will not be dead cold if I drop out of the lift band. At this height (approximately 500 foot) you will have limited time to find a landing spot and virtually no height to attempt an emergency air start if the motor doesn’t start.

The Highway Lookout

Higher up (900’ to 1000’ or more) the lift is further out at from the ridge face and is easier and more relaxing to fly although it will taper off in strength the higher you go.

I have achieved a personal best of 1700 foot in the centre of the ridge and 2500 feet along the higher ridges opposite Main Arm Valley and a personal best time in ridge lift of 3 1/2 hours for a total of 0.12 tacho time or about 7 minutes engine on. I’m sure that given the right conditions that five hours would be quite achievable, after all it was done way back in the 1930’s as indicated in the history section.

Middle Main Arm Valley

Ridge Flying Rules

1. All turns should be made away from the ridge face to prevent you from crashing into the ridge face or being carried over the back into sink and turbulence. If you have enough height fly out from the ridge and try a 360° turn and see how far you can actually drift back with the prevailing wind in relation to the ground.

2. You should overtake another glider on the inside between the ridge and that aircraft as, according to rule 1, he might suddenly decide to turn out from the ridge to change direction. If there’s not a lot of room you do have a radio to advise your intentions or alternatively fly upwind and rejoin the traffic when safe to do so!

3. Approaching another glider “head-on” the glider with the ridge on the left shall turn right. (Alternatively the glider with the ridge on its right will go straight ahead!). Normally away from the ridge the “rules of the air” indicate that each glider has to turn to the right to avoid one another but just remember that if the ridge is on your right and you turn in that direction you would be turning into the ridge and might crash! We don’t want that, so your glider goes straight ahead and the other glider makes the right turn and “gives way”. Never assume that the other glider will give way, just like a car at an intersection! You should confirm by radio that the other glider has you visual and be prepared to take evasive action just in case.

4. Don’t fly lower than 100 feet (approximately 2 plus wing spans) above the ground or within 100m horizontally from a person, house or public road. Apart from being the agreed rule common sense dictates that you should not fly too close to houses as residents can be startled to find a glider just off their back verandah and can believe that we are flying dangerously or are invading their privacy by looking into windows (I’ve yet to be able to see the inside of any house but they don’t know that), there have been complaints in the past!

5. Don’t fly directly above or below another glider as you could be in each others blind spot. Again you should use your radio to verify that the other glider is aware of your proximity.

The Highway Bowl

Other Useful Tips

You will have a tailwind as you approach the ridge. This will increase the radius of your turn therefore approach at a shallower angle rather than perpendicularly so you don’t inadvertently drift behind as you turn. This will also help you to establish a crab angle to compensate for drift as you fly along the ridge.

Don’t drift too far behind the road or the ridge top as there maybe some turbulence or wind sheer. Similarly if the wind is at an angle to the ridge you will get better lift on the upwind side of any bowl or spur and you should fly wide of the downwind side to avoid possible sink.

Turns should be accurate and reasonably tight especially at lower levels where the lift band is narrower.

With a lot of north component in the wind the ridge often works better flying in a southerly direction but you may lose the lift in some areas when you’re coming back. Lift is not necessarily the same strength each way.

With a strong northerly component and a 15 to 20 knot wind you can get very gusty cross wind conditions on the airstrip which can result in some quite interesting landings – be warned!

Catching a thermal off a ridge face requires a different technique. You should do tight S-turns in the area where you believe thermal lift is always being aware of your speed in case you get sink in parts of the turn or on the edge of the thermal. Never turn into the ridge face until you are well clear of the ridge top when you can start doing full turns in the lift but you must stay aware of where the wind drift is taking you as you may have to return to the ridge against a headwind and through sink in the lee of the ridge.

With more than one glider on the ridge in close proximity use your radio to indicate if you are turning (give your call sign, position and the direction of your turn) and also indicate when you are leaving the ridge as the other glider doesn’t want to be left guessing where you have gone and/or talking to themselves.

Be aware of out landing sites along the ridge. You should never assume that the motor will always start!

Enjoy the Fun!

Mt Burrell

The McPherson Ranges (Part of the Border Ranges)

GFA rules on Ridge Soaring:

Page 7: 2009.gfa.org.au/Docs/ops/airradio.pdf

3 Responses to Ridge Soaring the Coorabell

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment

A Dutch lass told me of her friend fresh from Europe. He’d never seen the Australian outback before – straight off the plane at Sydney, another to Cairns and another to Burketown – and the following morning she dragged his body to the saltflats in the pre-dawn light to see something “interesting”. On cue, like a rolled up blind it came at them, stretching across the horizon. Faster and faster, large and then huge, the sky darkened, the wind howled. Tears on his cheeks, awe and terror in his voice, he spoke. Apocalypse.

Inspired by this tale, I rigged a sound system to the glider and awakened sleepy Burketown with Valkyric Wagner soaring low and fast on the Morning Glory. Bah tan de doo dah, bah tan de dooo dah…

This great ridge-soaring clip uses that same music:

Low Flying Sailplanes from James Harvey on Vimeo.

Morning Glory over Burketown

Brillig, John! Greatly appreciate your efforts.